Twice a day the Pacific draws back its surf-fringed curtain to reveal a secret world brimming with fantastical creatures that John Steinbeck described as “ferocious with life.” They have to be. Only the fierce can survive in the harsh borderland between the tide’s highest splash and deepest pools. In this kingdom claimed by both sea and land, waters rise, waves pummel, predators pursue, and real estate wars rage.

“The intertidal zones are some of the toughest neighborhoods on the planet,” says Hollis Bewley, coordinator of the Stewards of the Coast and Redwoods Tidepool Education Program, “Every animal has to adapt in some weird or wonderful way to an incredibly difficult environment.”

After years of wandering amid puddles left by the retreating sea, I‘ve come to think of their tenants’ survival strategies as superpowers that defy mere human capabilities.

Consider the formidable challenge of clinging for life—and for a lifetime–to a rock battered by white-caps and winds. Mussels manage this feat by producing a kind of superglue that hardens upon contact with water to create silk-like “byssal” threads that can secure them for twenty years or longer. Barnacles have evolved a more acrobatic form of attachment. After swimming freely as tiny larvae for a few weeks, they choose a hard surface—boulder, pier, hull, whale—and head plant onto it. With no eyes or hands, their agile legs pop out of their protective shells to forage for food.

Ochre sea stars, elegant in rich jewel tones, have a stomach-turning superpower–literally. Crouched atop a tasty clam or mussel, they use their suction tube feet to pry open the bivalve’s shell just enough to slide their stomach inside, emulsify the soft body, and slurp it down for dinner. Another enviable ability: If any of its five arms are injured or broken, the sea star can regenerate a new one.

The giant green anemone (from the Greek for “flower-animal”) relies on its fatal beauty. This beguiling predator deploys its petal-like tentacles to lure, stun, and sweep tiny marine organisms into its mouth. Confronted by a threat, the supple dancer morphs into warrior mode and fires stinging harpoons.

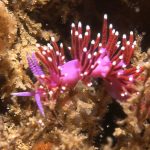

Soft-bodied, shell-less aeolid nudibranchs (for “naked gills”) flaunt eye-popping colors, stripes, polka dots, and ruffles. These aren’t whimsical fashion statements but a warning to predators that the pretty little sea slugs have ingested stinging cells called nematocysts that make them unpalatable–and potentially deadly.

As a docent on school field trips, I’ve asked young explorers which superpower they’d like to possess. Some opt for the giant green anemone’s stunning trickery; others, for the nudibranch’s clever costumes. Then I point out that, despite ingenious survival skills, no tidepool dweller could survive on its own.

Each has a unique niche and role, but all are interdependent. Even when fighting with or preying on their neighbors, intertidal residents are maintaining a crucial balance within their watery world. They also share one common superpower: the ability to adapt to ever-changing conditions. Ferocious with and for life, they testify to nature’s astounding diversity, creativity, and resilience.

Is it any wonder that beach rovers of all ages venture out with the tide to peer into self-contained universes and marvel at the stories unfolding before our eyes?