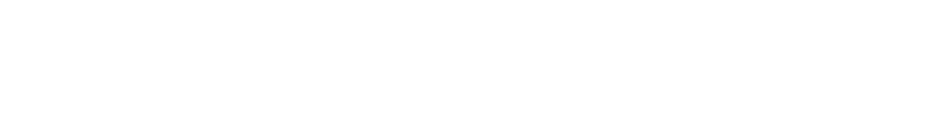

The purple sea urchin I’m holding doesn’t look like an environmental terrorist—more like a domed pincushion bristling with spikes. I can’t look this echinoderm (pronounced ee-KINE-o-derm), a cousin of sea stars and sea cucumbers, in the eye. It doesn’t have any. Nor does it have a brain, heart, backbone, or blood. Yet urchins, among the most ancient animals, date back 450 million years and inhabit every ocean on earth.

These days “purps,” nicknamed for their deep violet coloring, have gained a sinister reputation as “perps” for their role in devastating the lush kelp forests along the California coast. As a volunteer with a research team headed by Dr. Laura Rogers-Bennett of the Bodega Marine Lab and Dr. Dan Okamoto of UC-Berkeley, I’ve gotten to know the purps outside and in, from prickly exterior to intricate interior.

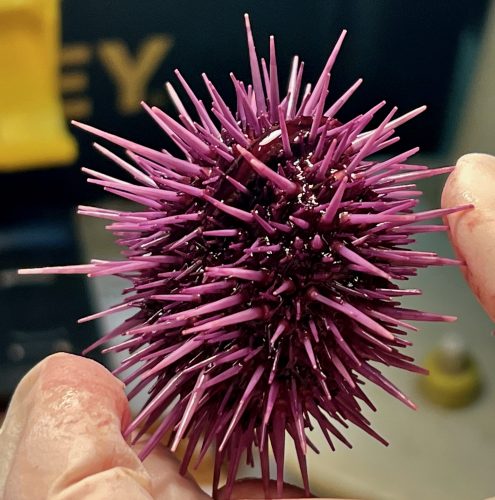

Urchins, whose name derives from the French for “hedgehog,” have long fascinated scientists. In the fourth century B.C. the Greek philosopher Aristotle marveled at their unique chewing mechanism, similar in design to the five-sided lanterns of his day.

The complex structure, dubbed “Aristotle’s lantern,” houses five razor-sharp teeth that can gnaw through rock, metal, and the ultra-tough ties securing tanks in the Lab. Opening and closing like the claws of an arcade’s prize-grabbing machines, these mighty jaws inspired the sediment-sampling pincers of the Mars Rover.

The urchin’s impressive vascular system transports sea water to hundreds of narrow tube feet that secrete a water-proof adhesive to secure them to a hard surface. To move, the urchin releases a solvent to free each foot—a process repeated over and over and over again. Also scattered among the urchin’s protective spines are pedicellariae, long thin stalks with wrench-like tips that grasp floating bits of food. Like a bucket brigade, spikes and tube feet ferry the morsels into the urchin’s mouth.

About a decade ago a wasting syndrome wiped out the predatory sea stars that had kept the urchin population in check. Then water temperatures rose and weakened the giant bull kelp, one of the urchins’ favorite foods.

With their numbers skyrocketing, hordes of hungry purps chomped their way through the “sequoias of the sea” that had provided food and shelter for myriad species. The once vibrant ocean floor has been transformed into desolate urchin barrens where these underwater zombies can survive without food for years.

“Before we can restore a healthy balance, we need to understand more about how purple sea urchins respond to rising water temperatures and food availability,” says Maya Munstermann, a UC-Berkeley doctoral student whose lab team has weighed, measured, dissected, and sampled gonads and genes from more than 1,500 purps. “How is climate change affecting their growth and reproductive capacity? How can they persist when kelp and other food sources have disappeared?”

After observing hundreds of dissections, I can attest to this brainless, heartless, spineless creature’s drive to survive. Sometimes after its shell is cracked in two, the just-severed halves of an urchin shuffle eerily toward each other, as if trying to become whole again.

Even in death, purps leave their mark. In the wild the bones of urchin-munching sea otters turn a ghoulish shade of purple. In a lab their body fluids stain researchers’ hands. Recently a coastal artisan began offering workshops in using dye from foraged urchins to create elegant silk scarves.

From purp to perp to fashion accessory? The indomitable urchin’s saga continues.

Photo Credit: California Academy of Sciences